Philipp Lehmann published Desert Edens: Colonial Climate Engineering in the Age of Anxiety in 2022, the same year that the UN officially declared it will be impossible to prevent temperatures from rising 1.5C and causing irreversible human and ecological damages.

We are living in an anxious age. The feeling is in no small part due to the impending collapse of social and environmental ecosystems all around us. The planetary scale of the problem has been mixed with a case of digital learned-helplessness — the only remaining solution is retweeting yet another graph of historic temperature records, or atmospheric rivers, or specie extinction. This is our zeitgeist

We consume the slow destruction of the world from fast feeds. This has made magnanimous proposals like cloud seeding, reforestation, and rerouting of rivers seem like viable and urgent solutions.

Philipp Lehmann reminds us that this condition is not new. The 19th century imbedded a spirit of environmental anxiety into the European ideology and brought bespoke engineering visions to the masses. Lehmann looks particularly at French and German colonists. Both recorded the historic incongruity of the climates within their new territories and conceptualized ambitious plans to terraform the environments for maximum profit.

Some projects include:

The Sahara Sea

“[The] Sahara Sea would have flooded a number of low-lying desert depressions in southern Tunisia and Algeria with water from the Mediterranean… the resulting man-made lake would have covered an area of about 16,000 to 19,000 square kilometers (or about 6,200 to 7,300 square miles; somewhere between the size of Connecticut and New Jersey). The French engineer expected easier and safer access and new marine trade routes to the inland areas of French Algeria, but also a climatic transformation that would turn the desert into fertile land for agriculture and European settlement.”

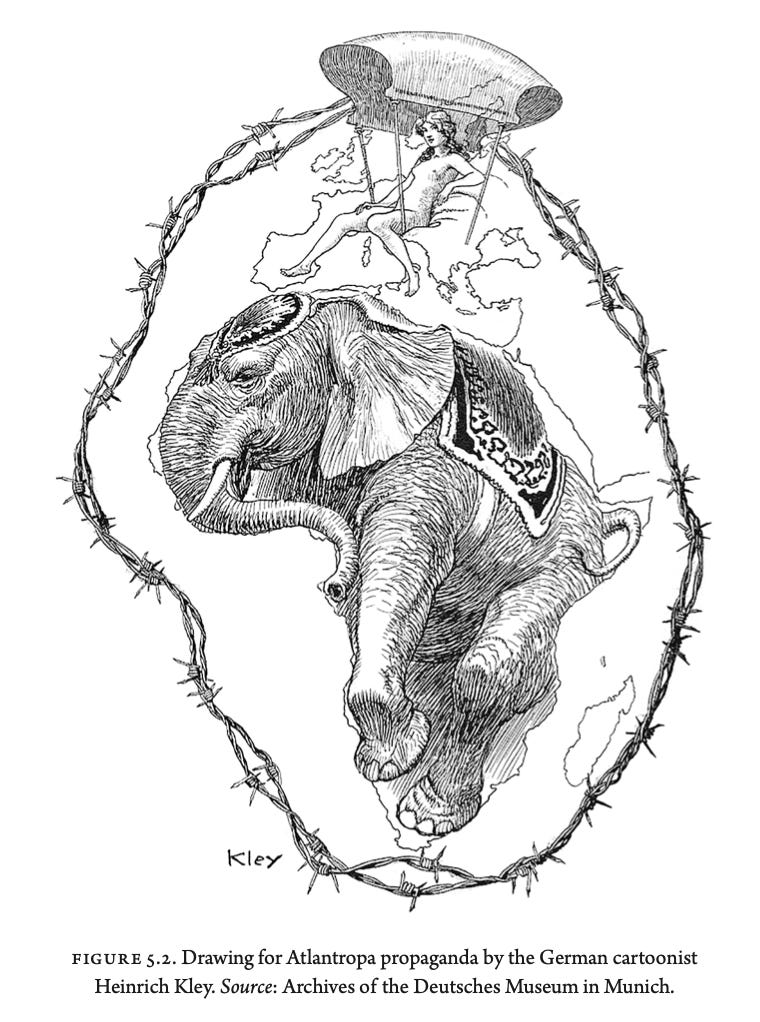

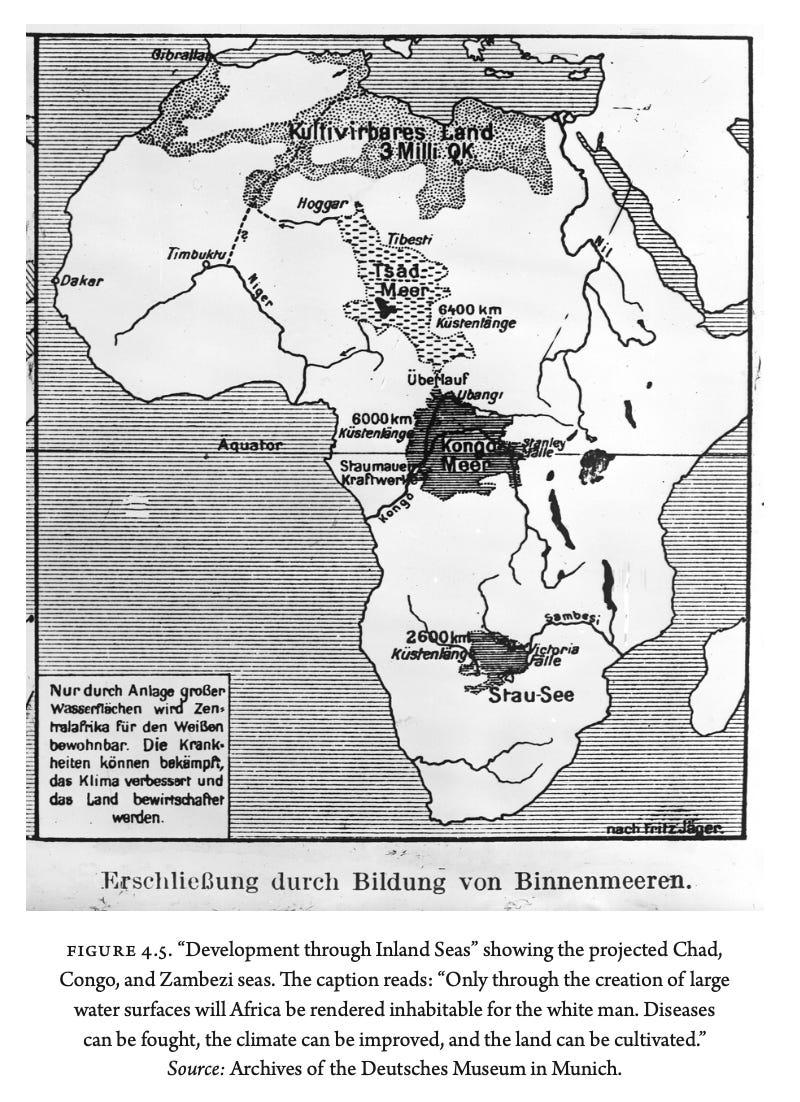

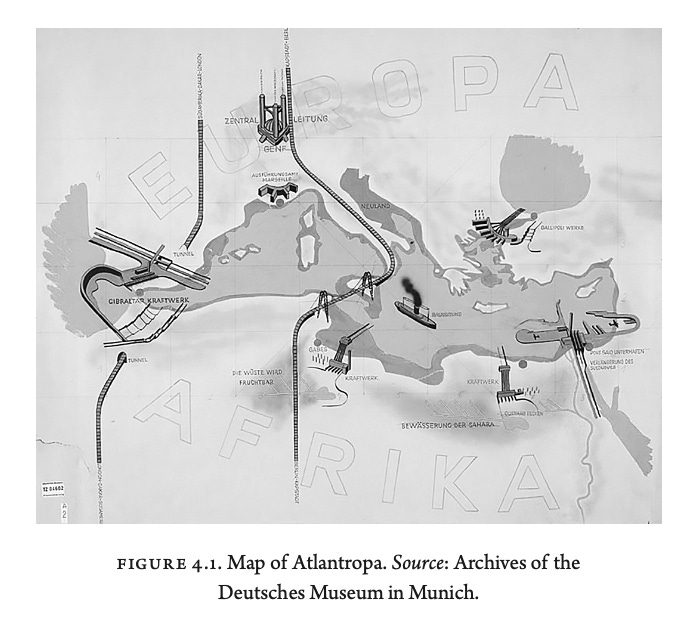

Atlantropa

“Atlantropa, centered on a giant dam at Gibraltar… Sörgel proposed a complete barrier between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean, linking Europe and Africa… combining “Atlantic Ocean” with “Europe” and evoking the lost city of Atlantis… Atlantropa actually surpassed the mythical city: upon construction, it would expose new land around the Mediterranean basin, change climatic conditions as far afield as Northern Europe, and produce vast amounts of hydropower to fuel the irrigation and complete environmental transformation of North Africa.”

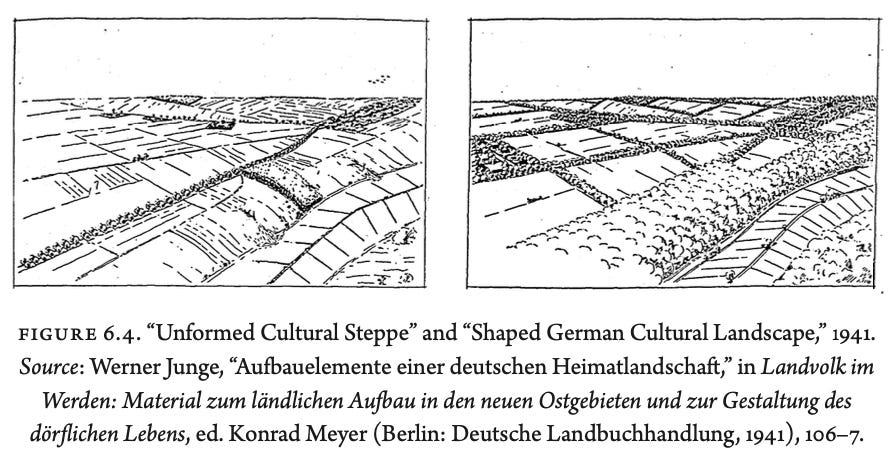

3. Combatting" “Steppification” (or Eastern European Desertification)

“Among the most infamous schemes of the Third Reich, the Generalplan Ost, or “General Plan East,” stands out for its totalizing rationale that sought nothing short of a radical and all-encompassing transformation of landscapes and their inhabitants… of what today are Poland, the Baltic States, Russia, and Ukraine—or the “bloodlands”… The Nazi planners, however, went much further, exploiting the common anxieties over environmental decline to rationalize erasing the histories, the landscapes, and the people of occupied colonial territories.”

We had the privilege to speak with Phillip and ask him a few questions about why he started this project, the similarities between climate anxiety then and now, and how we should think about technological optimism today. Here are some highlights.

Roman: What inspired this project?

Phillip: This project started more than 10 years ago. It was a time when there wasn't that much literature on German colonialism in Africa yet, particularly on Namibia. I tried to understand how Germans actually tried to make sense of these extremely different environments that they encountered, particularly compared to where they came from).

Through that, I came across a couple of rather humble water engineering projects, which just outlined how to collect water from the seasonal downpours.

But through that literature, I came across this plan by a South African engineer named Ernest Schwartz who had planned a much bigger project on the border of what is now between Namibia and Botswana to flood the flat land with water, and use it for irrigation purposes. That itself was a very large project but it didn't really concern climatic conditions. This led to more utopian geoengineering projects in North Africa and that's really where I came across a lot of ideas about changing climates.

Colonial administrators had collected data on changes of the African climates, noting that it was becoming more arid. Some argued at some point what is now the Sahara was a rainforest, and the desert took over.

So many of the bureaucrats hoped for a reverse, perhaps you could also use technology to turn the desert back to what it had been before: a luscious forest. In fact, from Germany to France, colonial administrators were extremely concerned about the climate conditions of their colonies, designing complex geoengineering plans to adjust the environment for their goals.

Roman: You really emphasize this general feeling of anxiety that all of these colonial administrators are exhibiting about the climate, which feels very... current, everyone is terrified about the climate. How different this feeling today?

Phillip: I think the 19th century is very closely connected to a general anxiety that came with the colonial push to occupy new lands and open new markets. The very different environments they encountered made it incredibly difficult for colonial administrators to turn a profit on the new occupations.

The first thing the French and Germans consider when landing on shore is the land's economic potential: soil quality, environmental conditions, rainfall. So the very first surveys of a new colony were usually done exactly on this. Oftentimes this is where the anxiety began. The Europeans were unfamiliar with the dry climates, they didn't know how to establish the European industry, they did not find what they knew or what they were looking for... how were they going to pay back for the journey? Climate anxiety of the 19th century is primarily anxiety of how to pay back colonial investors.

Jesse: Your book overlaps extreme environmental pessimism with powerful technological optimism, which creates this paradoxical understanding of what to do next. So, what do we do next?

Phillip: The ideas about climate change that people had in the 19th century are very different from what we now know about climate change. Early on these were just regional environmental ideas. There was really no sound scientific basis to think about a global climate pattern yet.

I do think though that you know can trace much of the environmental anxieties from the late 19th into the 20th century. They're often connected to kind of an unease of where modern society is heading, with expansion. Of course, now that has transformed into GDP growth and obsession with productivity. But no politician wants to talk about how we must stop the economy from growing, right? That's a terrible thing to talk about, but that's ultimately what we would have to do.