Belize bonds and Cantonese Miami

A collection of stories about climate infrastructure around the world

In 2007, the African Union launched an initiative to build a 5,000-mile-long wall of forests across the continent. While it’s still in its early phases, and there are a mix of opinions on the eventual success of the project, it has been undeniably successful in utilizing and encouraging local entrepreneurship.

Some farmers in Niger developed a technique to recover the land by digging crescent shaped ditches called “zai pits” which capture and redirect rainwater more efficiently. Another initiative is called “assisted natural regeneration,” and involves fencing in plots for greenery to grow, then using it for beekeeping or growing crops.

A women-led group is growing Moringa trees, which have nutritious leaves and edible seed pods. The pods can also be ground to powder, turned into oil or used to filter water. This group even has their own shop where they develop and sell soaps, cookies, and cakes.

There is a lot of doubt that this wall will be completed. Fifteen years after it was begun only 15 percent of the area has been restored, but work continues.

In 2021, Belize was on the brink of default. The country had reneged on its loan multiple times, and none of the underwriters were willing to hold the toxic debt. Now, the hot financial instrument is maintaining a peculiar trade — Belize gets preferential debt terms and funds for development, and international finance gets to brag about protecting the Belize coast line.

This is called a debt-for-nature swap and it involves restructuring sovereign debt in exchange for debtors’ investment in nature conservation.

Belize’s commitments included astronomical fees, an agreement to spend US$4m annually until 2041 on marine conservation efforts, and the doubling its so-called ‘marine protection parks’ from 15.9% of its oceans to 30% by 2026.

It’s easier to understand the bond in reverse. Alejandra Padín-Dujon explains:

As the final step, investors buy Belize’s restructured debt in the form of de-risked “blue bonds” (so named because they are related to marine conservation).

Before that, the US International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) de-risks the previously unattractive blue bonds (making them more saleable to investors) by insuring them. In other words: if Belize fails to pay up, the US government will step in.

Call it a Red-White-&-Blue Bond, because the ultimate backer of the debt (the only reason it can be floated to international investors), is the guarantee from the US government.

The Belize Blue Investment Company (BBIC)—an entity of The Nature Conservancy—and Credit Suisse issue the blue bonds to pass along Belize’s unappealing debt, which they hold, to diverse new owners.

BBIC and Credit Suisse hold Belize’s debt to begin with because of an arrangement to loan Belize US$364 million, conditional on new commitments to invest in marine ecosystems. Belize uses this loan to buy back a pricey ‘superbond’ it has issued.

Belize is able to buy its $553 million superbond at a steep discount because the original investors are persuaded to take only 55 cents on the dollar for it, likely in order to boost their own green credentials.

The cost of engineering this financial frankenstein? $85 million — or about $75 million more than originally planned. The profit will cover Credit Suisse excel services, insurance premiums to the IDFC, the premiums to private-sector reinsurers, and at Belize’s interest payments.

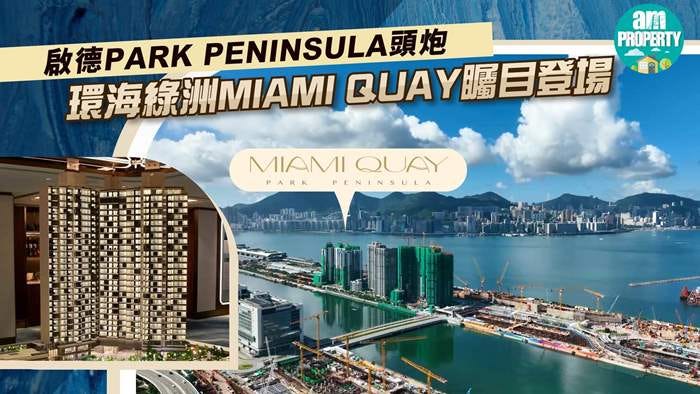

Since Miami is doing so well, Chinese developers have decided to replicate it in Kai Tak, Hong Kong. Miami Quay I Park Peninsula is a development plan to “take Miami as a design concept” Eastern coast of Central America and build a luxurious urban seaside cityscape.

The 320 acre development will be situated on a peninsula. It will include a Miami-inspired apartment complex called “Club Miami,” which boasts art, play spaces for children, swimming pools, and a gym. And, of course, there will also be a cruise terminal.

Local news sources say that Egypt is diverting water from the Nile and building what will eventually be the longest man-made river in the world. It is meant to address the country’s water and food shortage, as well as the consequences of “Africa’s Largest Dam” being constructed on the Nile but within control of Ethiopia.

Egypt’s new river will be 115 kilometers (71 miles) long with 12 transport stations along the routes that will send the water to be treated. The Middle East Monitor says it will cultivate almost 9,200 square kilometers of land in the Western Desert. No international news outlets have covered the project.

We talk a lot about aquifers in this newsletter, so just as a review of what an aquifer is and why we care: Aquifers are like underground natural pipelines for fresh water, collected through thousands of years of rainfall. They transmit and natural filter water through different rock surfaces.

Aquifers are one of the most important sources of fresh water in the world. Unlike lakes, Aquifers are not instantly refilled by rainfall, and in the short term, are a scarce and quickly depleting resource.

North America’s aquifers are in danger. One of them, called Ogallala, provides ~30 percent of all crop and animal production in the US. According to Sam Knowlton, who specializes in agriculture and regenerative farming, Ogallala’s water supply has dropped by 75 percent and is on track to dry up in the next 70 years.