Dunes, Domes & Renaissance Dams

A collection of stories about climate infrastructure around the world

As sea-levels rise, coasts are rapidly disappearing. A 2018 study showed that 24% of the world’s sandy beaches are already eroding at unprecedented rates of 0.5 meters each year. But new research shows that sand dune restoration projects can help slow coastal erosion.

Scientists erected a fence around a dune, planted seeds of native dune plants, and over a six-year period, they found that the volume of sand had increased. Interestingly, the first phase of the study involved them bringing in sediment from other localities to make the beach larger. But the fencing — the process of trying to maintain existing sand — was more effective. This is big news in the coastal erosion world, half of which is attempting to dredge sand from the ocean floor in order to keep a tight grasp on their rapidly disappearing land, but the sand is slipping through their fingers.

The finding offers exciting potential for a relatively simple solution. So far, projects are popping up in the Gulf of Mexico, New York, New Jersey, and the Pacific Northwest.

Futuristic domes have popped up in the UK county of Cornwall as part of the Eden Project, which is growing what is essentially a botanical garden and rainforest habitat. But it’s what’s under the domes that’s exciting. The Eden Project is entirely powered by the country’s first deep geothermal energy project.

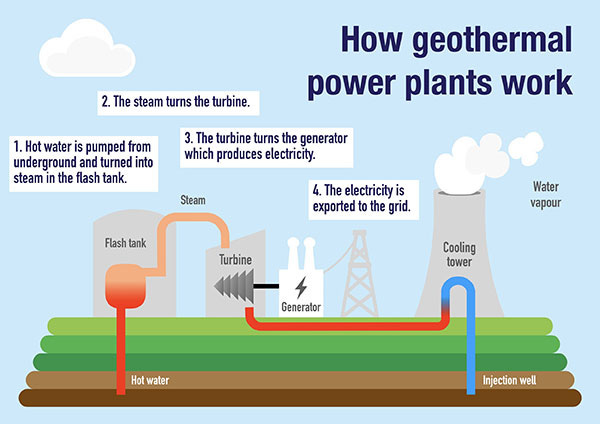

If you’re not acquainted with how geothermal power works, it involves drilling a well that goes into the Earth’s core. Hot water is then lifted out and siphoned into a machine that extracts the heat. The cooled water is re-injected back down into the earth.

The average depth of geothermal wells is about 30-120 meters (100-400 ft). The UK has some shallow geothermal projects around the country but this is the first to reach 5km (~3 miles) below the Earth’s surface and pumping up water that reaches 200C (395F). The deeper you go, the hotter the water, and the more energy it provides. Geothermal is expected to reduce the project’s energy bills by 40 percent.

In mid June, Ethiopia announced it would begin filling the reservoir behind the Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD), which is the largest on the continent. The countries along the Blue Nile (Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia) are all prone to droughts, causing controversial negotiations around the project — both Egypt and Sudan are concerned that Ethiopia will have a stranglehold over their water supply. Egypt has referred to the GERD as an ‘existential threat,’ which seems fair given they rely on the Nile for 97 per cent of their irrigation needs.

Talks began when the project broke ground back in 2011, and while there is now a consensus as to what defines a drought, the dispute over the appropriate legal mechanisms to deal with one continues. Egypt wants a guarantee the Ethiopians would release water from its reservoir should water levels fall below 35-40 b.c.m. per year; the Ethiopians would prefer to leave that choice to their discretion. Talks continue, with President Sisi repeatedly calling for compromise.

The invasion of Ukraine has severely damaged the country’s agriculture sector. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Food Programme (WFP) just announced a joint program to clear farmland that has been littered by mines and explosive remnants to allow farmers to regrow their crops. They are working with the Fondation Suisse de Déminage (FSD), which is an NGO focused on safe de-mining. The focus is on smallholder farms with 300 hectares or less, as well as rural families growing food for themselves.

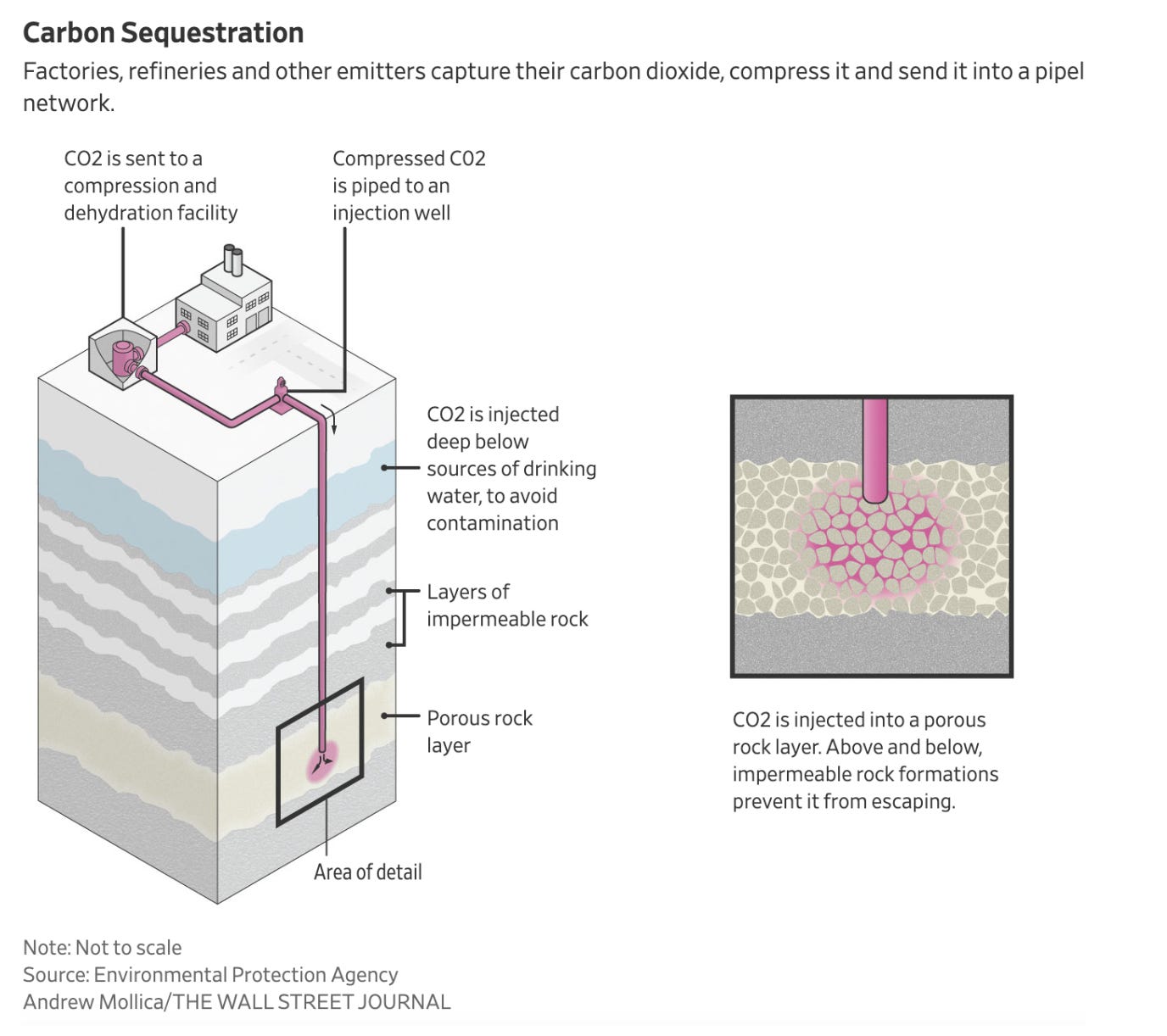

The United States Department of Energy recently committed USD$242 million in funding for nine CO2 storage projects, with another $2 billion waiting in the pipeline. With the raft of additional subsidies and tax incentives from the IRA, underground carbon storage is now much more attractive to fossil fuel companies. Big oil is moving fast to lease as much land as possible.

Oil companies are now leasing hundreds of thousands of hectares for carbon storage — the WSJ has put the number at around 480,000 acres of land for CO2 storage in Louisiana and Texas alone. Commentators are saying it's like witnessing the shale boom of the early 2000s all over again. Right now there are only four CO2 injection wells with operating permits, but another 100 are in review.

The process generally involves taking CO2 from the air, compressing, then injecting it underground. In recent years, an array of new technologies have emerged with creative ways of capturing and storing carbon. The industry is moving forward in leaps and bounds — not least because oil companies have realized that injecting carbon into older oil fields with declining yields is a means of temporarily boosting production. Today some 20% of total oil production uses this method, which is known as Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) .

The International Energy Association estimates we would need to shut away over five billion tons of C02 to avoid a climate disaster by the end of the century.

It’s a nascent field, and some environmentalists say we don’t fully know the consequences of injecting carbon down below. WSJ’s Phred Dvorak quoted Kirk Barrell, an oil-and-gas geologist: “Now the strategy is: Lock it down; we’ll figure out the details later.”

Let’s keep our fingers crossed on this one…

With contributions from Ian Trueger.

Ian Trueger is a writer based between London and Marseille. He has a background in anthropology and has had work published with the BBC, the FT, The Washington Post, and Quartz among other publications. He is currently working on his first book, which is an anthropological history of pork.