Kelp, Horses, & Geodesic Domes

A bi-weekly collection of stories about climate infrastructure around the world

Forty years ago, Bob Lee, a retired oil engineer, developed six adjoining geodesic domes on a beach in Cape Romano in the Gulf Coast of Florida. They have been partially stranded in the ocean for years, and on September 28, 2022, Hurricane Ian struck the final blow and they became fully submerged under water.

They, unlike most things at that time, were built with climate change in mind. Their spherical walls were meant to be an asset during storms — the wind would have a less fatal effect on the structures, and rain would seamlessly drip into the drainage system built around the structure. The water was filtered and reused, there were solar panels that supplied their water heater and hot water, there was a photovoltaic system (which turns light into electricity) and the fridge ran on a battery.

It survived Hurricane Andrew in 1992 but in 2004, water started rising up the concrete pillars. By 2005, Lee sold the home. Hurricane Wilma hit a few months later and the coastline eroded enough to destabilize the foundation. The pillars were permanently underwater by 2007 and the tenants were replaced by marine life. The domes never came down, despite orders by the county, and now they live entirely under water, a poetic reminder that even the best adaptations require land to survive.

A company called Tidal is using cameras, computers, and machine learning to support the ocean’s most ingenious natural infrastructure: seagrass.

Seagrass, seaweed, kelp, whatever you want to call it, is crucial for carbon dioxide sequestration. The World Economic Forum said that seaweed is better at absorbing CO2 emissions than trees are.

Tidal — owned by Google — is using computer vision and underwater cameras to autonomously identify the carbon capacity of seaweed and “lend credibility to marine-based carbon credit projects and markets.” The software can even tell the weight, maturity, and health of surrounding fish.

It will take a while for them to be able to confidently assess the amount of carbon that a patch of seagrass can carry, but once they do, the research can be used to promote seaweed businesses and subsidies for seaweed growing and mangrove restoration.

French towns are bringing back the horse-&-buggy in response to the energy crisis and the stresses of modernity. French locals are eager to prove this is not a pastoral past time, but the future of transportation. Everything from garbage trucks to school buses are being drawn by a horse.

“It’s absolutely not a return to the past,” said Vanina Deneux-Le Barh, a sociologist at the French Institute for Horses and Riding. “It’s a sustainable development approach, about respecting nature and welfare in new, innovative ways…”

The world has talked a lot about carbon offsets, and consequently planted a lot of trees, and those two things have made everyone feel like the world was really changing. Well, 10 years on, the results are in and offsets have done very little to reduce emissions.

If United Airlines flies from New York to London, the company might hypothetically determine that a flight emitted 1000kg of CO2 into the air. One hardwood tree can sequester 1000kg of CO2 by the time it reaches 40 years old. So United Airlines might plant 10 trees to hypothetically capture 1 ton of carbon in four years.

As you can tell, there are too many hypotheticals in this equation. Without global standards and accounting regimes, everything from how a company counts the emissions of a flight and it's proposed timeline, to how it calculates the sequestration-potential of a spruce is up to the ESG consultants at an individual company.

Satellite analysis is now showing that this offset regime is mostly a convenient accounting truck and a net negative for the world. Ordering a seaweed salad on your flight is probably as good of a sequestration strategy as planting a tree.

A town in Inner Mongolia, called Kangbashi, seemed like it was built to make the news: world class architecture, stadiums suitable for international audiences, and luxury housing. But instead, a bunch of outlets covered it as a “ghost town,” a “stillborn city,” and a “failed utopia.” It turns out this representation wasn’t completely fair.

The site, which was started in 2004, wasn’t ready for journalists when they arrived around 2008. Four to six years is neither reflective of the Chinese urban planning strategy nor of the global urbanization rates. The town intended to finish building all of the necessary infrastructure before hundreds of thousands of people moved to the entirely new city.

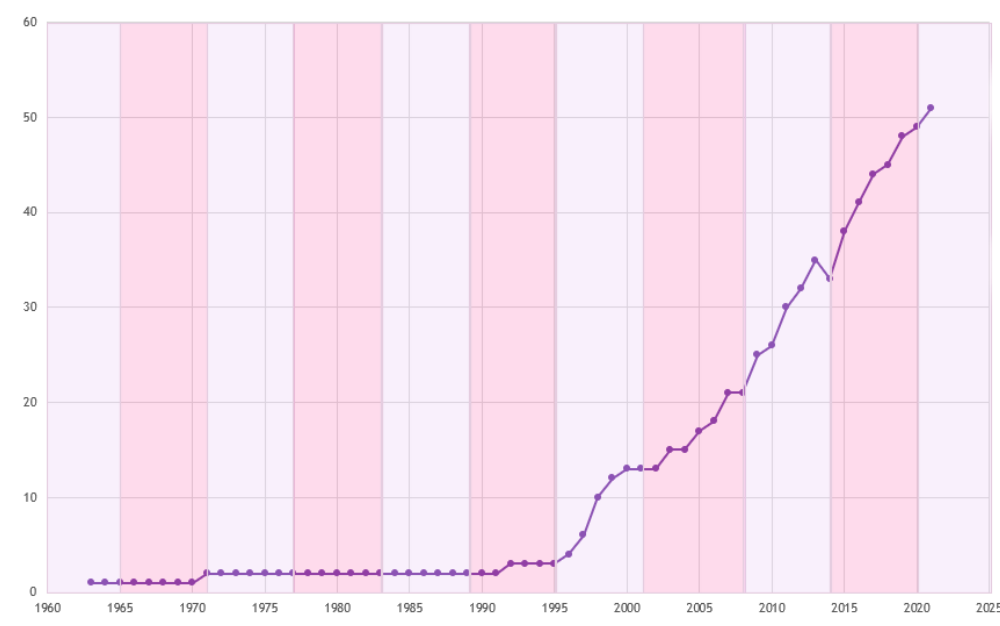

News outlets latched onto the idea of a “city built for no one.” But today, almost 120,000 people live in Kangbashi with around 18,500 new students enrolled in schools, according to data collected by Bloomberg.

As the world invests in new, sustainable city models, one of the primary concerns is how to get people to live there. Journalists will be on the prowl for wasted money and resources, but perhaps cities like Kangbashi — of which China has many — provide a cautionary message: be patient.