Seasteading's Fatal Contradiction

The responsibility lost between the cracks of freedom and a feasible future

If you click into any seasteading website, you’re greeted with a dream. Cozy glowing pods with stargazing showers dot the Gulf of Mexico, hotels and shopping centers sit on the bottom of the ocean floor near Louisiana, a mall floats unnervingly still on the waters near Puerto Rico. This is where people have the peace of mind to do yoga every day; this is where bliss lives.

Seasteading companies, which aim to build permanent dwellings at sea, are promising to usher in the next phase of humanity with a rhetoric of eco-restorative, climate friendly homes on the water. However, the industry’s anti-regulation, libertarian ideology puts it at odds with the necessary controls to protect the ocean. The question is less about whether seasteading can be ecologically beneficial — or at the very least, neutral — but whether or not its champions are willing to put the rules in place to make sure it will be.

“We are building something that we believe can offer a next phase for humanity,” said Connor Firmender, Head of International Business Development at Ocean Builders, which is building floating pod-shaped homes near Panama. “And we are doing it in a way that’s eco-restorative.”

Despite these promises, the foundational ideology behind seasteading is anti-regulation. When it comes to choosing between the freedom to litter and a policy that bans people from letting their waste fall into the ocean, for example, seasteading companies have either said that they will choose freedom or say it’s not their responsibility.

“The Seasteading Institute is not going to be supporting projects that don’t protect the environment as long as I work here,” said Carly Jackson, Deputy Director of the Seasteading Institute, which is the ideological home for the movement. But when asked if she would support regulations in order to protect the environment, she said no. “It’s more a violation of my own values to try and control other people.”

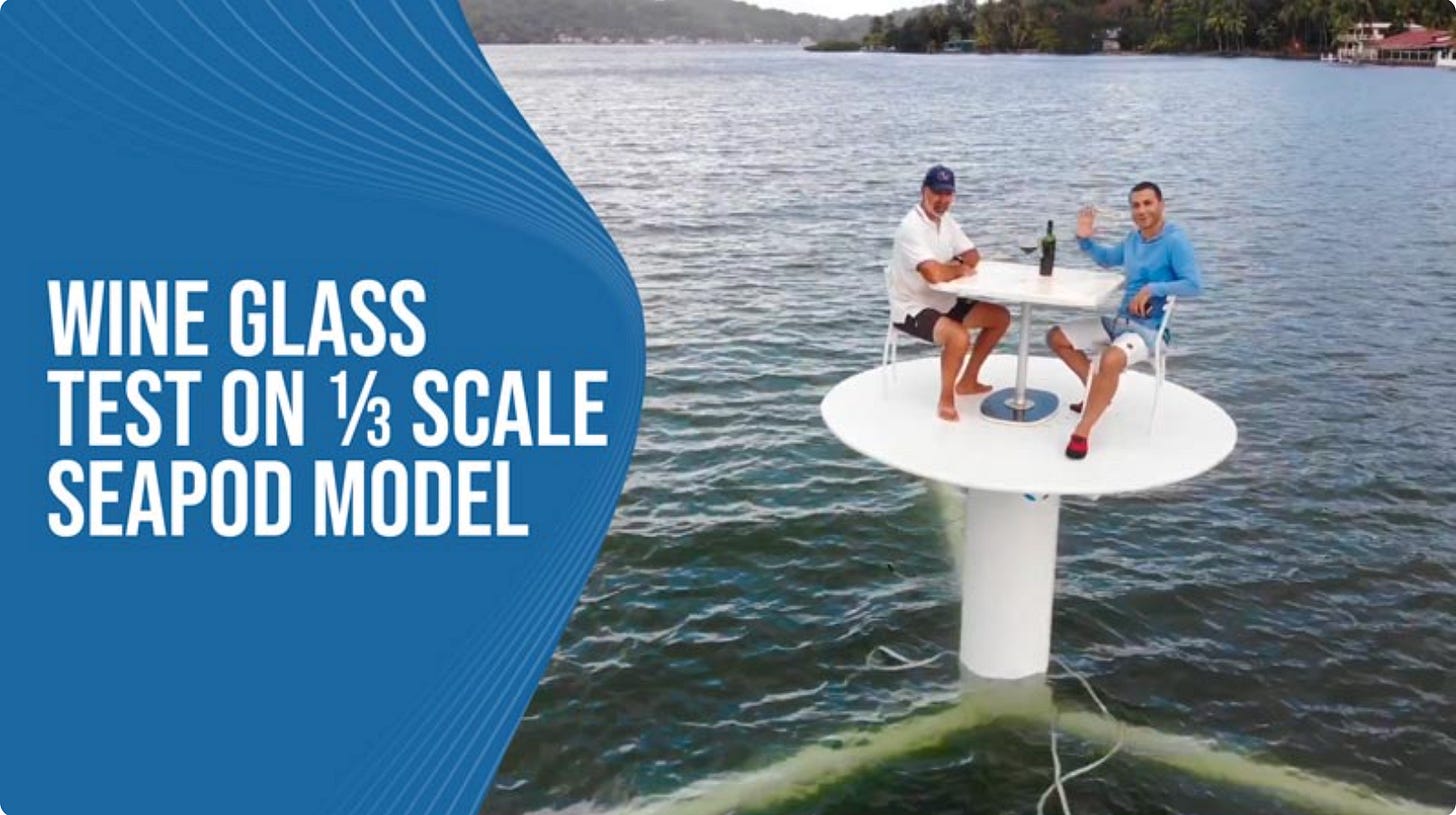

Ocean Builders says that its pods will create a “habitat for ocean life to thrive” by offering “creation and supplementation of natural ecosystems.” The company conducted a mini test of this in 2021 in which they left a model in the water for two years to see what life it would attract. They found barnacles, coral growth, sponges, etc.

While it’s true that life attaches itself to artificial reef structures, there is no readily available peer-reviewed research showing that these particular homes will be eco-restorative. In addition, the test didn’t include people living on the structure for those two years, therefore failing to account for the additional presence of humans and all of our incredible and creative capacity to destroy life.

Individual companies believe that responsibility lies with the owners of the seasteads. “When most development companies go out and build, they’re not really asking the question: how do I keep control over this? They are just building to meet customer specifications and they’re building to meet consumer demand, and that’s what we’re also doing.” said Mitchell Suchner, Chief Operating Officer of ArkTide, a company building a dome structure to accommodate housing for 400 people and commercial and public spaces off the coast of Puerto Rico.

The industry seems implausible — a sparkly luxury entrepreneurial venture that will never take off. But the movement is finding ways to get just enough approval to comfort investors, and some are establishing partnerships with governments for the time being.

The Seasteading Institute believes that they will have to work somewhat within the legal system in order to get investment. A seasteading flag, according to Jackson, would allow for “a legal path that has the least amount of burden.” Every vessel needs to be registered with a flag under maritime law. It allows for them to move about the ocean freely, go through inspections, and dock where necessary. In a press release in 2021, the Institute wrote, “If we flag seasteads, more than two-thirds of the earth’s surface is legally opened as a frontier for free societies.”

Other companies are getting their homes qualified as resorts, which have more flexible environmental requirements.

Ocean Builders gets their homes certified as house boats through the Panama Maritime Authority. While in Asia, two different countries are willing to let them bypass the house boat certification because their homes are for resorts and ecotourism. Every country and regulatory process is different, but Firmender says “house boat certifications don’t give a shit about environmental protections.”

Suchner of ArkPad said that they endorse whatever the Seasteading Institute says regarding the ideology of the movement. For now, they are making plans to work with the government of the Philippines to provide more affordable housing. They are hoping to sell their first homes for around USD$200,000, but will decrease the price as they scale. “When we mass produce these, they will be significantly less — I am thinking of a six-figure number that starts with ‘1’,” he said.

While they are working within the world’s regulatory framework for now, these organizations don’t see themselves as providing resorts and second homes forever. Their goal is to be part of the rise of cities on the sea.

“I imagine living in a city floating on the water will have the same trade and entertainment and diversity and excitement of a city but on the ocean,” said Jackson. “Most seasteaders want a community and they want to build it with the values we have.”

They foresee a freedom unique to floating. “If my house floats,” Jackson says, “I can just leave. There’s an impermanence and I can just break away and move.” This also allows for an ideological freedom. If a person doesn’t like the direction a community is going in, they can detach and join or start another one. And therein lies the rub: how do we make sure the ocean — the new theoretical home of these dreams — is protected in a world where a group of people who reject environmental protection can simply float away and create their own community?

This future becomes even more desirable when framed in the context of climate adaptation.

The Seasteading Institute adopted climate change as an issue it could address around 2016, when it traveled to Tahiti in French Polynesia to create a legal structure for ‘seazones’ that would have a “special governing framework.” They said that the industry would “provide environmental resiliency to the millions of people threatened by rising sea levels, provide economic opportunities to people in remote and economically deprived environments, and provide humanity with new opportunities for organizing societies and governments,” according to a statement that is no longer available on the site but was accessed in 2017 by Raymond Craib. Craib wrote the all-encompassing book on seasteading, “Adventure Capitalism.”

The industry represents the allure and dangers of the rhetoric of climate adaptation — of a future where we accept that while the climate crisis will make land uninhabitable, it’s ok because we have found an even better alternative: the ocean. But if you even lightly tap the bubble around that dream, everything falls apart.

Somewhere in the process of walking this tightrope between legality and libertarianism, responsibility might just float away too.