The Simple Magic of Old Aqueducts

Lisbon's Águas Livres is a relic of a time when infrastructure couldn’t defy gravity

In a northwest neighborhood of Lisbon sits a retired water reservoir where you can’t tell the floor from the ceiling. Magnificent arches are mirrored with such precision on the still waters below that for a moment you’ll wonder how people walk on those arches.

But then, you’ll see the spooky soft outline of a green staircase descending into the depths. If you’re anything like me, you might feel a tingling sensation in your feet.

King João V (pronounced Zhoh-OW) planned the Mãe d’Água (Mother of Water) das Amoreiras reservoir in the 18th century and it was the center of an ornate Roman-styled aqueduct system that served five different municipalities of Portugal until the 1960s. Today it’s a UNESCO site and part of a museum — a relic of a time when infrastructure and art went hand-in-hand. When I visited, it was a backdrop to an “immersive” and aggressively impersonal Frida Kahlo exhibit for high school students.

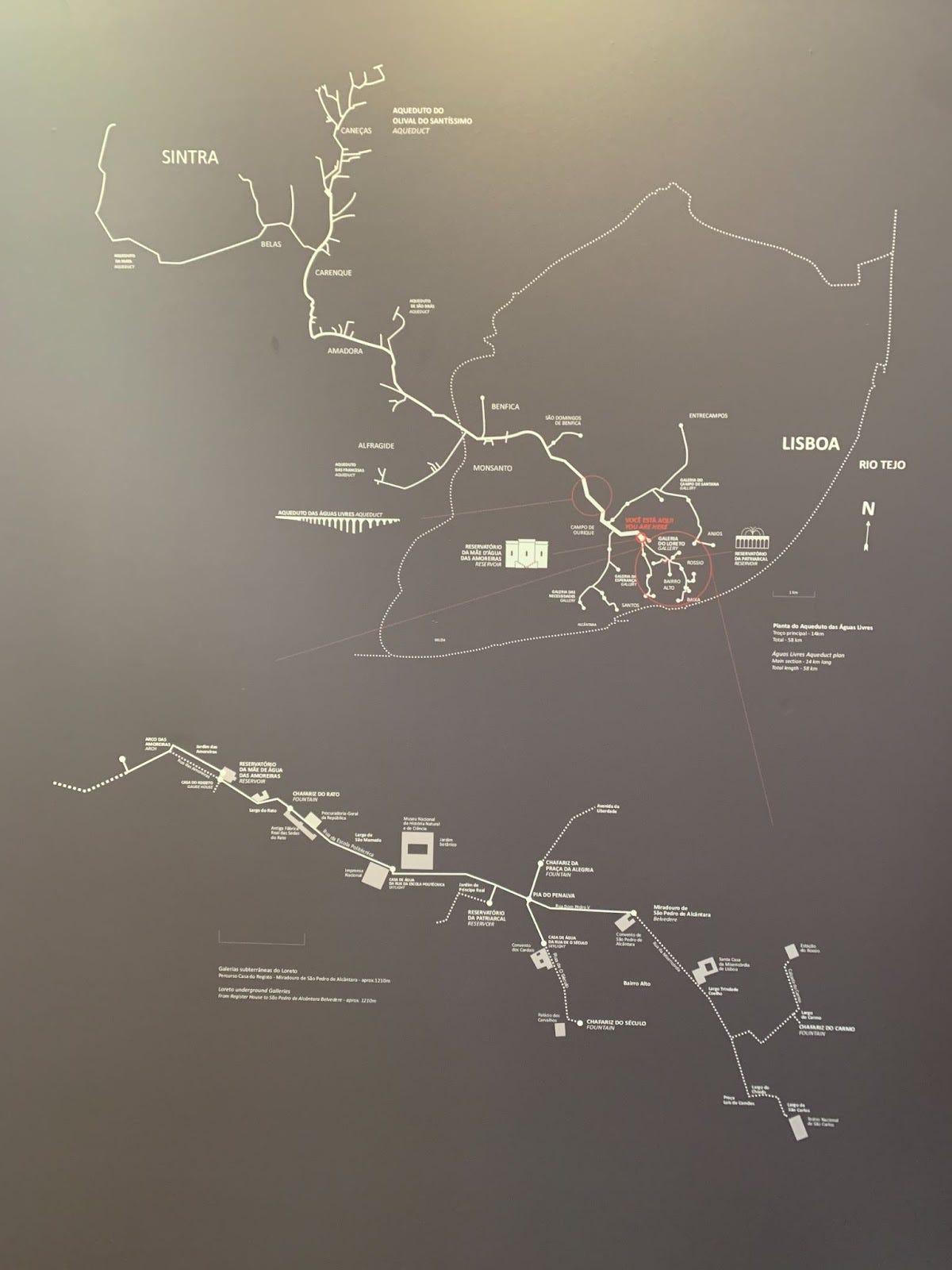

The Águas Livres Aqueduct, named because it was meant to capture “free waters” (águas livres) from the mountains, was built between 1731 and 1799. Using gravity alone, it transported water from the cultivated fields and pine groves of a luxurious mountain town called Sintra to the West and into Amadora, Lisbon, Odivelas, and Oeiras.

Lisbon struggled with drinking water supply since its earliest inhabitants settled there — the closest estuary had a regular influx of seawater. Outside of the city center, people grew desperate. In 1728, city administrators started collecting a tax on staple food products to raise funding for water works that would alleviate insecurity.

A mix of European architects passed the torch over the years, but a steady flow of locals put blood, sweat, and (probably) tears into building it. Between that and paying a tax on bread, the aqueduct became a personal project to the people of Lisbon.

Twenty years later in 1748, the aqueduct was already bringing water into Lisbon. In the years following, fountains popped up all over the city and more canals were built to increase the capacity. In 1755, the structures survived an earthquake, adding to its status as a national symbol of achievement. At its height, the system covered 36 miles of under- and above-ground conduits and reservoirs.

This reservoir system doesn’t really count as a nature-based solution in today’s jargon. It involves harsh “grey” architecture rather than soft “green” infrastructure changes. But there is something charmingly natural about the Águas Livres.

The aqueduct was made to fit into its environment. The bridges have stylized pointed archways of varying heights that straddle towns, highways, valleys and rivers without looking out of place. In some parts, the columns stand in between buildings and houses, making you question which came first: the aqueduct or the building below it.

The aqueduct is a national symbol. It has made its way into oil paintings and “Visit Lisboa” pamphlets. One man, Diogo Alves, was an infamous thief and murderer who operated in the aqueduct hallways, earning the title “Aqueduct Murderer.” (I’ll spare you more details but that link is entertaining).

The central Mãe d’Água reservoir clearly wasn’t just for holding and transporting water either. It was made to be looked at, stood in, and appreciated. The outside of the Mãe d’Água has classical decorative gargoyles and the inside feels more like a Church than a water reservoir, with its tall arched ceilings, grandiose columns, and cool stone. Directly across the entrance is a bulbous grotto cascade with a stone dolphin on top. The cascade and the dolphin were built with stone from the area where the water originates. Upstairs and outside is an easily accessible rooftop where you can see panoramic views of Lisbon. This structure is not some remote resource building — it is, and was always meant to be, a museum.

Modern pumping systems as well as watershed from the Alviela River allowed water to be brought directly into people’s homes in the 1880s and ultimately made the Águas Livres superfluous. It wasn’t entirely decommissioned until the 1960s, however. The infrastructure built in the 18th century left room for modernization. In the 19th century, they added iron pipes, siphons, water treatment stations and steam-powered pumping stations. The technical aspects of the aqueduct evolved with the country while the architectural structure, which is apparent as you walk throughout the city, continues to impose the memory of this impressive feat on present-day citizens.

Roman-styled aqueducts were a feat of engineering all over the world, from Portugal to Greece to North Africa to Turkey. But nature-oriented engineering comes in all shapes and sizes. We have talked in Edifice about underground gravity fed aqueducts in Xinjiang that were dug by hand. Turkey relied for centuries on a series of open channels and raised canals.

This type of engineering represents a time before technology could reverse the pressure of gravity. They were an 18th century version of a nature-based solution, one that incorporated architecture into the urban skyline and directed resources with respect to the slope of a mountain.

There doesn’t seem to be any chatter about whether or not the aqueduct could be used again, but its solid earthquake-proof structure and independence from modern technology makes you wonder if, in an emergency, this kind of ancient engineering could one day come to our rescue.